New research from the University College Dublin in Ireland, shows that when planning for future forest management, the policies that are put in place to respond to climate change may have a more significant influence on harvesting patterns and product volumes than climate change itself.

The research conducted by Anders Lundholm, a PhD student, with postdoc Dr Edwin Corrigan and Lundholm’s supervisor Professor Maarten Nieuwenhuis, is part of ALTERFOR (Alternative models and robust decision-making for future forest management) – a multi-national EU Horizon 2020 funded project created to develop forest management approaches that are resilient to the developing climate crisis. His research focused on the Barony of Moycullen, home to Ireland’s largest contiguous forest – the Cloosh Valley forest.

The Barony of Moycullen is a complex area. The Cloosh Valley forest itself is dominated by Sitka spruce planted in the 1970s and 1980s alongside a smaller amount of Lodgepole pine. Thanks to its beauty, the forest and its surroundings, the Barony is also a hub for tourism and local recreational activity. “The area is astonishing,” Lundholm explained. “You get the combination of the forest and the green and open landscape with mist rolling in from the sea. Some stands are yellowish due to nutrient deficiency, and the area is dotted with lakes, ponds and watercourses,” he said, noting that because the trees were planted on peat soils, productivity is naturally low for large sections of the forest. Sharing the Barony of Moycullen is several populations of Ireland’s freshwater pearl mussels, a native species that can reach 15 cm in length and live for up to 140 years. Sensitive to changes such as river flow, siltation, nutrient loadings, and dependence on salmonid fish for their life cycle, the mussels have earned the rather unfortunate status of being in the top 400 most endangered species in the world and are protected in Ireland by law. Aerial fertilization, which could increase forest productivity, is banned to protect the mussels.

Balancing mussel protection with the recreational desires of people, all while maintaining an economically viable forest, is already challenging. With climate change altering precipitation, temperature, and other weather patterns that can impact the forest, meeting that challenge is becoming even more complicated.

Changing weather conditions is not the only climate change issue a forester needs to consider, however. Policies to minimize global temperatures may involve the development of a ‘bioeconomy’ – increasing the use of sawlog and pulpwood products for construction and biofuel to replace other products that have a more substantial carbon footprint. Invariably growing demand for wood-based products also increases their value; a switch to a ‘bioeconomy’ should also minimize our carbon footprint and thus, global temperature increases.

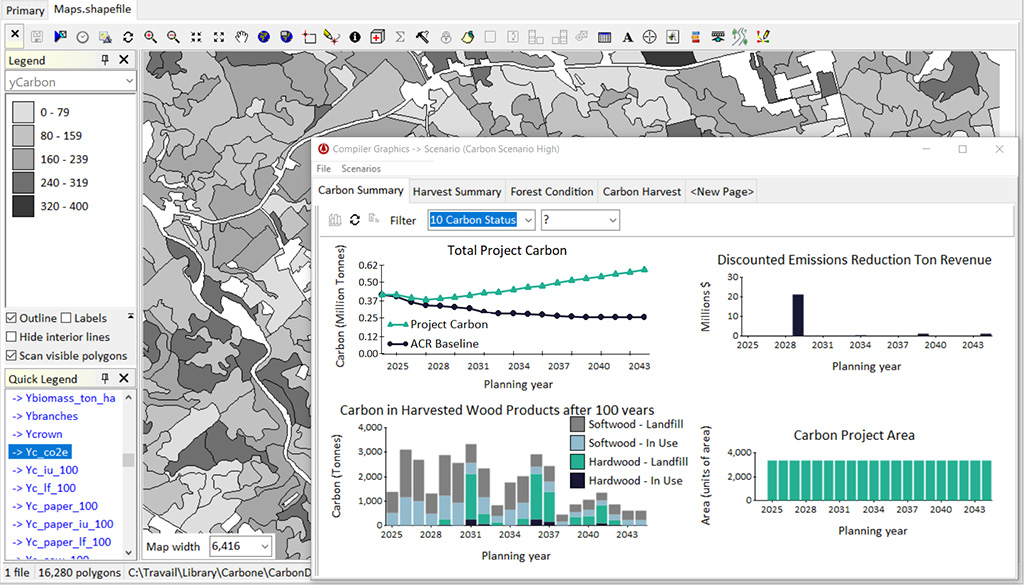

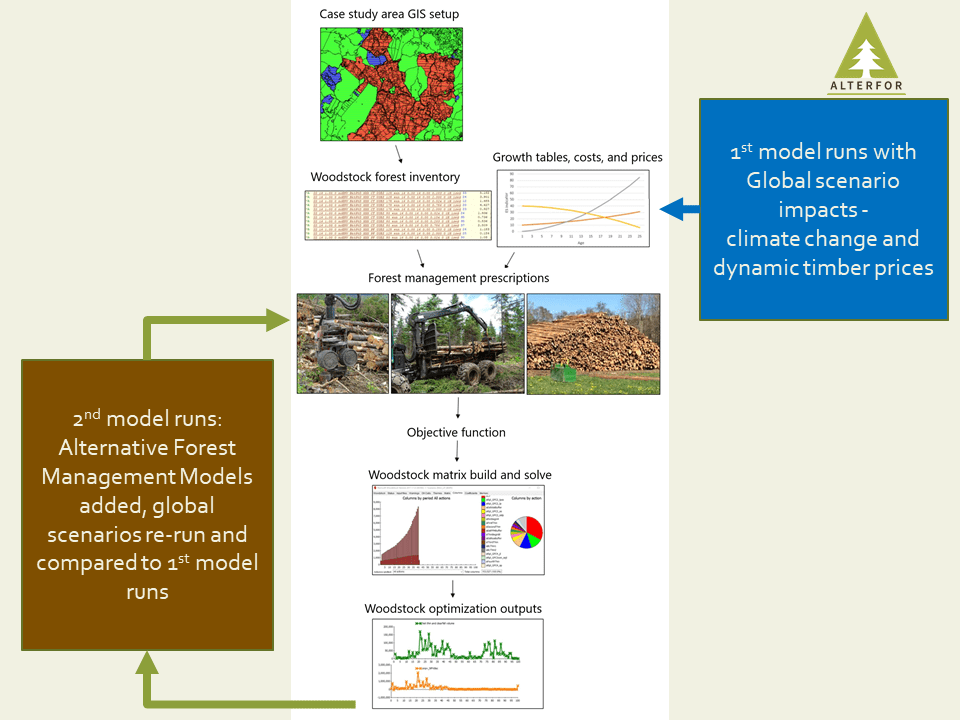

Lundholm explored what climate change and a move towards a bioeconomy could mean for the management of the Cloosh Valley forest over the next 100 years. Forming the backbone of his analysis was Remsoft’s Woodstock Optimization Studio – a prescriptive analytics and decision optimization platform for forest management planning. For Lundholm, programming flexibility was crucial in his work;

The beauty of Woodstock is that you can define various attributes to your specific conditions. It’s a platform you can utilise for forest planning, no matter where you are in the World,” he explained.

Alongside climate change impacts on tree productivity and potential growth in the bioeconomy, Lundholm incorporated current environmental policies and desired forest futures identified by forest manager Coillte Teoranta as well stakeholders such as NGOs into scenarios for future forest management.

The research suggests that the combination of current environmental policy, future demand for wood from a growing bioeconomy, and the changing climate means the Cloosh Valley forest will have to change to Lodgepole pine, not Sitka spruce dominated system. Climate change will result in some areas simply becoming unsuitable for Sitka in the future while creating more favourable conditions for Lodgepole pine. However, the most significant consideration for future forest management are the predicted bioeconomy changes and current environmental policy requirements.

Although Lodgepole pine tends to be used for pulpwood, which commands low prices, policy-driven demands will make Lodgepole pine more financially attractive. “If you look at climate change, it has a negative impact on net present value in harvest volumes, but due to the projected increases in the bioeconomy, there will actually be more harvesting,” Lundholm explained.

Lodgepole has another trick up its sleeve – it can grow into a merchantable crop without fertilizer on nutrient-poor sites like the peats found in the Barony of Moycullen. Unlike for Sitka, additional inputs won’t be needed for the trees to reach their full potential, making Lodgepole more compatible with legislation to protect the freshwater pearl mussels. As for the recreational potential of the forest, tourists and locals alike will be pleased to know that these management scenarios allow the forests to continue providing beautiful scenery.

Lundholm highlights that there are several climate-change issues that we don’t have data for, but are important for forest managers. For Lundholm, the biggest unknown is the situation with pests; “Pests are predicted to become a bigger concern with climate change and with increased global trade, but we don’t know exactly what pest is going to come in and what’s it going to do,” he said. As an example, Lundholm explains that in parts of Ireland where drought may become commonplace, Sitka is likely to be stressed and thus less resilient to pests.

Ultimately, models and simulations cannot tell a forestry manager precisely what to do, but they do allow managers to consider alternative scenarios in their planning. Lundholm notes that although there are uncertainties surrounding timber prices and how trees will respond to climate change at local scales, exploring potential scenarios and identifying trends now can help managers adapt to a rapidly changing climate and policy landscape.

LEARN MORE:

-

This work was supported by Remsoft’s Educational Partners Program, which aids academic research and teaching initiatives that increase understanding and improve practices in sustainable forest, land, and asset management.

-

Find out more about the Educational Partners Program, and how to become a member.